"Burnversions" Reviewed by Washington City Paper Art Critic Louis Jacobson

"St. Louis Cathedral" by James W. Bailey

"St. Louis Cathedral" by James W. Bailey

"Aloha Motel" by James W. Bailey

"Aloha Motel" by James W. Bailey

Above images referenced by Mr. Jacobson in his review in the Washington City Paper.

"Woman at the Tomb" by James W. Bailey

"Woman at the Tomb" by James W. Bailey

Above images published in the Washington City Paper.

Welcome to Hoodoo, America!

"Yeah, you rite, cher! My prices just went up!" - The Right Reverend James W. Bailey

Management at Black Cat Bone is excited to report that the Right Reverend James W. Bailey's current exhibition, "Burnversions" , has been reviewed by art critic Louis Jacobson of the Washington City Paper.

Brother James is currently on vacation at an undisclosed isolated fishing camp in the bayous of Louisiana just outside of New Orleans working on a 50,000 word epistle review of the Hoodoo film, Skeleton Key, and has issued the following statement by satellite phone:

"I am deeply grateful to Mr. Jacobson for his thoughtful review of 'Burnversions'. I lined the floor of the exhibition gallery with blessed brick dust ground from from a brick from St. Louis #1 Cemetery in New Orleans and issued a prayer to the spirits to invite Mr. Jacobson to cross over it. I so greatly appreciate him doing so.

I am also very appreciative of the Washington City Paper publishing his review and thereby transmitting the positive power of Hoodoo through the print and online media to the many wounded bodies and minds of those who have been burned in their personal lives - you know them when you see them, as they walk among us in sadness and anger over the emotional crimes that have been committed against them.

Oh, children, just touch the paper the review is printed on and know that 'Burnversions' stands at the ready to liberate your lost soul through the spiritual energy of burned photographs.

Are you tired of thinking about that person that screwed you over, lied to you, cheated on you, broke your heart and twisted your mind with their games?

If so, child, healing is on the way. Just send me those photographs of all those bad, mean and evil people that have burned you and let the Hoodoo power of 'Burnversions' set your spirit free from all that pain.

On a personal note, I also want to say that I'm especially honored that Mr. Jacobson mentioned my name in his review in the company of Mr. Pete Towndsend - a man Who has always had his mojo working right!

I hope all who read this will consider participating in the 'Burnversions' collage. Please send your photograph of the person who has burned you to me by October 15. Simply write on the back of the photo what the person did to you. Please see the 'Burnversions' project web site for details.

God Bless all."

Washington City Paper Vol. 25, No. 34 Aug. 26 - Sept. 1, 2005

The Medium is the Message by Louis Jacobson

“Burnversions” - At the Reston Community Center to Aug. 31

When we look at photography, we mostly consider the image—the things it portrays, the style the photographer has used to capture them. Only rarely do we consider the physical aspects of the medium to be an integral part of a photograph’s artistic impact. And only in the work of an artist like James W. Bailey do we find photographs in which the artistic value of the print actually exceeds that of the image.

Bailey, a native Mississippian, has worked extensively in New Orleans and now lives in Virginia. His past projects have grappled with drive-by shootings in New Orleans and the Southern African-American tradition of the bottle tree. His current 16-work exhibition at the Reston Community Center showcases the technique he calls “rough edge photography,” in which Bailey deliberately sabotages his film at multiple stages to produce one-of-a-kind prints. According to his artist’s statement,

Bailey’s experimental...technique involves exploring the “death of chemically developed negatives and prints” through the use of found 35mm source cameras he purchases in thrift stores.

His process incorporates the violent manipulation of unexposed film, developed negatives and prints. Undeveloped film may be subjected to intense heat or pin pricks through the film canister. Developed negatives are burned, scratched, slashed or cut, as are the prints. In some cases, the original negative is melted onto the final print. The found camera that is used to shoot a particular narrative series of source photographs is frequently smashed upon completion of the series.

This may sound as showy and mindless as Pete Townshend’s smashing his guitar at the end of a show. But Bailey’s process is intellectually grounded—it’s partly a reaction to the sudden dominance of “clean” digital photography—and it creates emotionally weighty and visually compelling artworks. Though Bailey began practicing rough-edge photography only in 2001, he writes that it emerged from a searing experience he had when he was 11:

I watched a farmhouse burn down on property near my grandfather’s farm in Mississippi. I pulled from the wreckage a smoldering wooden box that contained a collection of scorched family photographs. I extinguished the fire from the photographs, spread them out on the ground and arranged them in a square, one next to another. It was the most haunting thing I have ever seen. The charred remains [were an] image history of a whole family. Burned remnants of mythology.

Blackened eyes peering behind charcoal. Smokey residue smeared over lost memories. I have never forgotten the image of the collage I created that day. There is no one photograph that could convey the emotional impact of that collage.

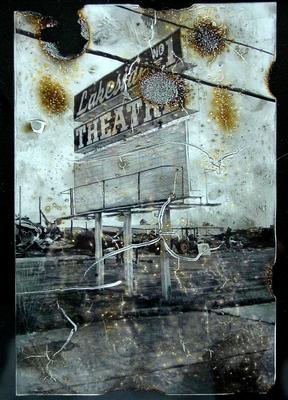

The subject matter of Bailey’s images in the Reston show is predominantly cemetery statuary—angels and religious symbols, mainly—though a couple of street scenes from New Orleans are included as well. The cemetery images have a moody, introspective cast that fits well with the project, and the hellfire evoked by the scarring resonates with the religious imagery.

Still, rarely have the nominal subjects of a photographic project been so inconsequential. Viewers will lose themselves not in the imagery but in the random forces of chemical and physical desecration that partially blot out what is being shown. The works in the exhibition, most of them made in 2004, are so visually complex that they demand that viewers peer directly into the print from just an inch or two away.

Take Cemetery Savior II. It’s a combination of two separate views of a religious statue with arms stretched out, but the surface of the work is riven by blistering, browning, and faulting. White dots from pinpricks add a celestial touch, while a burned portion ends in a delicate wisp of charcoal that gives the work a sense of three-dimensionality.

Or take St. Louis Cathedral. In addition to faulting patterns, this photograph is marred by the partial peeling of its layer of emulsion. Bubbled, almost cellular-looking forms swoop and swerve in all directions; where the layer is detached entirely it leaves behind an enigmatic void. Other photographs feature a wealth of other unexpected effects—ripples, tears that look like tiny knife cuts, moldlike masses, fireball-style burn patterns, constellations of flares, and enamelized mounds of charred material.

Eventually, the statuary backdrops of the defaced images become somewhat monotonous, with the interspersed street scenes providingwelcome visual relief—as well as a suggestion of a direction in which Bailey might fruitfully take his technique further. In an image of a motel, the bricks of the unassuming building actually seem to be buckling and melting as you watch. And in a street scene photographed from inside a car, a pedestrian gazes blankly past the camera as the photograph seemingly devolves into what looks like a mess of spilled milk and bacterial colonies.

The show was designed to incorporate another project, also titled Burnversions, in which members of the public were invited to send Bailey a photograph of a person who had “burned” them, with the story of the incident written on the back. Without offering names or identifying features, these photographs were sliced and diced and put into a collage. When the show is taken down, the collage will be sent to a Hoodoo priest in New Orleans for burning “as part of a ritual of spiritual healing.” Bailey promises to scatter the ashes across the Mississippi River on Nov. 1—All Saints’ Day—so that “these ashes to ash memories...float down the Great River of Life to the Gulf of Mexico; and from there, across the planet, and hopefully, out of the mind and memories of those who have been harmed...”

The artist is an adherent of Hoodoo, so this process obviously has deep meaning to him. But Bailey has a habit of adding elaborate, interactive codas to his photographic work, and this show is no exception. (For the drive-by project, for instance, he didn’t stop at photographing passers-by at murder sites but rather went on to send the results to randomly selected residents of New Orleans and then record their reactions.) The collage-turned-burnt-offering may not appeal to everyone. But even those who don’t buy the “ritual of spiritual healing” line can still appreciate the boldly creative visual vocabulary that Bailey, with his arsenal of defacement, has brought to the photographic arts.